Avatar

Published Monday, January 18, 2010.The Na’vi have great big blue feet. Wait till you see those in 3D.

Avatar is a love story between a man and an alien. A romance of extraterrestrial proportions. The rest is a journey into fantasy.

I guess we all grow up with these kinds of movies, films that trigger the imagination and offer you a glimpse of alternate worlds and impossible landscapes. Sci-fi and fantasy filmmakers are obsessed with scenery. The physical world behind the narrative becomes a powerful element of the storyline.

The technological advancements in digital imagery have now made everything virtually, quite literally, possible. And still, for the generation that grew up watching the flying bicycles in E.T. and the archaeological adventures of one mister Henry Walton Jr., aka Indiana Jones, something may feel lost in the process. A sense of reality drawn from the physical representation of space as captured through visual storytelling and metaphor. Something entirely misplaced in many current productions, as in the digitally overdosed misadventure of Indy in The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

Avatar is very much centered on the recreation of a physical atmosphere. We are introduced to the splendid and hostile landscape of Pandora, an alien paradise depicted in full 3Delicious glory. For a film so overloaded with digital technology, James Cameron has the merit of never underestimating the material dimension of its environment. And still, with all its epic backgrounds, the finest moments in Avatar lie in Jake Sully’s intimate dreamlike experience: «Sooner or later though, you always have to wake up», says Jake as he begins to question where his true nature lies. The complexities of this transition – the blurry boundary between the human and the alien experience – regrettably, never fully become a main theme with visual, cinematic, implications. The digital hyper-realism of Pandora takes its toll on a desirable abstraction of the eye. Technology takes central stage over a more subjective and humane mise-en-scène.

Now, I’m a sci-fi nerd and I would recommend Avatar to everyone. It’s just so compelling at what it’s good at. It’s a film driven by passion for its world and characters, making no concessions to fully explore the many details of Na’vi culture, language and religion. It may have its shortcomings but, while it rolls, it’s a feast of popular cinema and one of the most imaginative cinematic experiences I can remember. Here is the kind of megalomaniac extravaganza that comes but once in a decade. And if you know what it was like watching a Star Wars movie as a kid, well then, you know that feeling.

It’s Pocahontas. No, wait...

Big boys with toys.

We are going to need bigger guns.

Director James Cameron setting the engines to warp speed.

Castle of Castelo Novo

Published Friday, January 8, 2010.

Luís Miguel Correia, Nelson Mota, Vanda Maldonado e Susana Constantino: Castelo Novo, Fundão, Portugal, 2008. Image credits: Fernando Guerra FG+SG.

Observing the recent work by AllesWirdGut for the roman quarry in the Austrian village of St. Mergareten, another project comes to mind: the intervention in the castle of Castelo Novo, in Portugal, by the architects Luís Miguel Correia, Nelson Mota, Vanda Maldonado and Susana Constantino (COMOCO).

The project is defined by an overlaying accessible structure located within the monumental district, drawing a path from the central square and the tower located on higher ground.

Here we find an architectural piece unrestrained from formal pre-definition, founded in the territory without compromising its integrity; a design that establishes a clear boundary between the ancient ruins and the new supports, needed for the appropriation of the visiting public.

A curious blend between architecture and landscape design, this small-scale project in Castelo Novo is an interesting affirmation of respect for the historical heritage while introducing new tensions and providing a more fulfilling relationship with the existing territory.

Don’t miss the full gallery on Últimas Reportagens, courtesy of Fernando Guerra, and the project details available at COMOCO and Habitar Portugal.

Luís Miguel Correia, Nelson Mota, Vanda Maldonado e Susana Constantino: Castelo Novo, Fundão, Portugal, 2008. Image credits: Fernando Guerra FG+SG.

AllesWirdGutt ROM

Published Thursday, January 7, 2010.

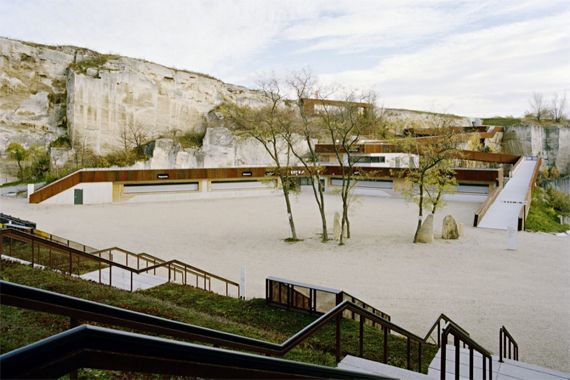

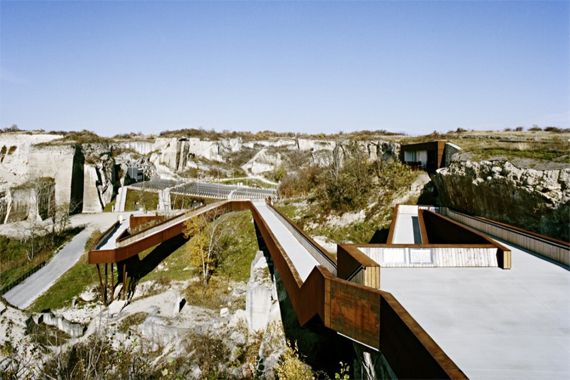

AllesWirdGut: ROM (Romersteinbruch), St. Mergareten, Eisenstadt, Austria, 2006-2008. Image credits: Hertha Hurnaus.

Three years ago I featured this particular project by AllesWirdGut here on my blog. The preliminary renders were nothing short of amazing, a staggering blend between architecture and landscape design. Now, ArchDaily presents a wonderful set of images courtesy of Hertha Hurnaus depicting this outdoor installation built upon the ancient roman quarry in the Austrian village of St. Mergareten.

This unusual location is used as a playground for cultural activities during the town’s yearly festival. The intervention upgraded the site by setting new accessibilities and several public installations. The natural qualities of this open-air auditorium are now enhanced with the overlaying artificial morphology designed by AWG, providing an overwhelming environment for the nighttime musical events that take place during the Summer season.

Don’t miss the data available on AWG’s website and download the PDF document attached as well.

AllesWirdGut: ROM (Romersteinbruch), St. Mergareten, Eisenstadt, Austria, 2006-2008. Image credits: Hertha Hurnaus.

Hybrids III

Published Monday, January 4, 2010.

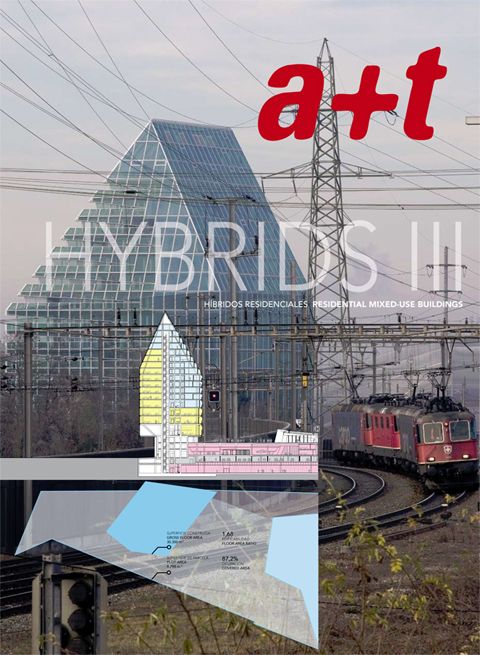

Hybrids III is the latest magazine from a+t architecture publishers.

Hybrids III is the latest double-issue from a+t’s Hybrids Series, focusing on Residential Mixed-Use Buildings.

Residential Hybrids are deemed as typological opposites to one of the most paradigmatic creations of the constructivist movement: the Social Condenser. Both typologies share their origins in the avant-garde era of the first quarter of the 20th Century. The Social Condenser, however, was born from State centered ideals under a recently created Soviet Union and would later become an extremely influential model for social housing in the European context, particularly after World War II.

The Hybrid was originated from a very distinctive set of circumstances, with its roots firmly embedded in the American capitalist system. Whereas the European city was guided by ideology, the American city was an outcome of the free flowing economy, a playground for profitability and speculation. The hybrid encouraged urban contact and cosmopolitanism, becoming consequential to a new paradigm of democratic city; a city born from multiple driving forces, integrating different programmes, different developers and different users.

Hybrids III presents an extensive investigation on the issue of housing integration in mixed developments, followed by a selection of 20 new projects that encourage the interaction of a variety of urban uses while also successfully combining private residential activities within the public realm. Featured projects include the works of MVRDV, Steven Holl, OMA, Neutelings Riedijk, Herzog & de Meuron and many more, carefully presented and analyzed through diagrams, technical drawings and construction details.

Visit a+t for additional information on this magazine and other publications.

MVRDV: Market Hall, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2004-2012.

Herzog & de Meuron: St. Jakob Turm, Basel, Switzerland, 2007.

OMA: De Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1998-2011.

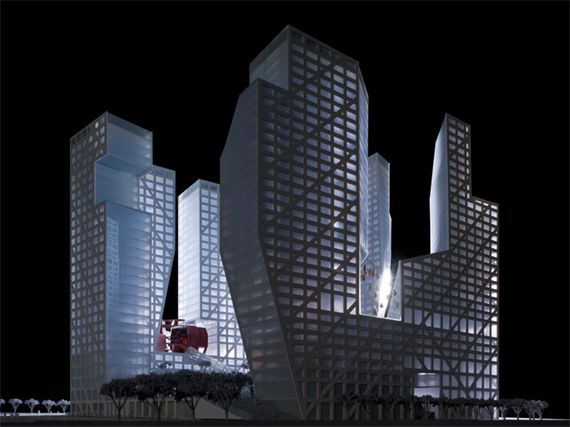

Steven Holl: Sliced Porosity Block, Chengdu, China, 2007-2011.

ENGLISH EDITION

The English-only edition of the blog A Barriga de um Arquitecto is no longer being updated. Please visit the main page to access new content, additional information and links.

ARCHIVES | ARQUIVO

September 2008 October 2008 November 2008 December 2008 January 2009 February 2009 March 2009 April 2009 May 2009 June 2009 July 2009 August 2009 September 2009 October 2009 November 2009 December 2009 January 2010 February 2010 March 2010 April 2010 May 2010 June 2010 July 2010 August 2010 November 2010 January 2011 February 2011 March 2011 June 2011 July 2011 October 2011 December 2011